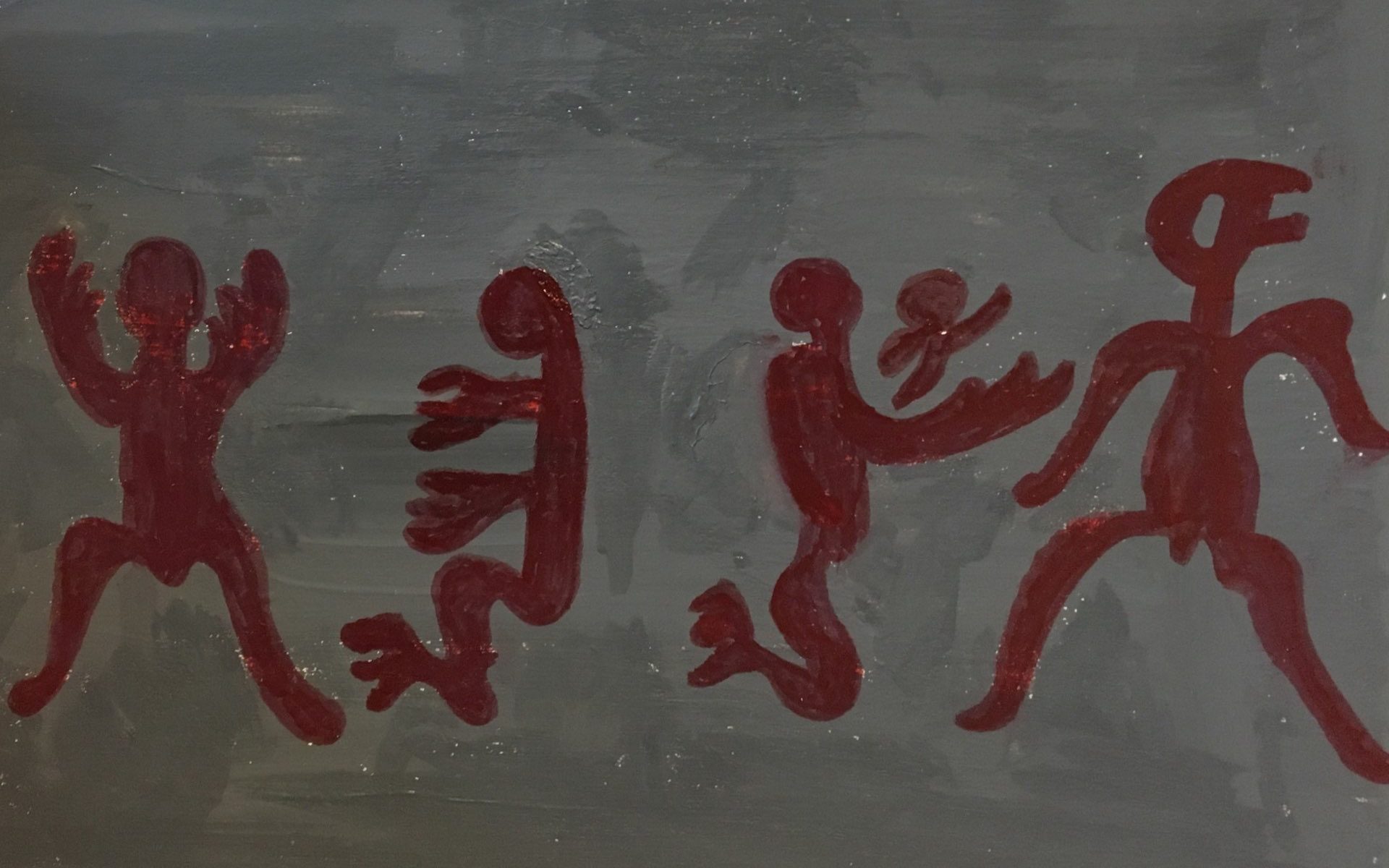

Illustration by Kuang, “Babies Unborn”

Note from Kuang:

As a curious stranger, as an old friend from another time, I sat down for a small chat with myself.

我忙于四处张望,却忘了回头看看自己。在这篇短文里,如一个素不相识的陌生人,又似一位久违的老朋友,我坐下来跟自己聊了聊。

I grew up in a remote village in Jiangxi. The village is very small with less than 200 residents. If you talk loudly enough, people living on either end of the village can hear you. It’s a 150-minute bus ride from my village to the county city, and the bus only runs once a day in the very early morning. I had to get up at five a.m. in order to catch the bus.

I have four elder sisters. This is quite rare for people about my age, because the Family Plan was extremely strict around the 1990s. Every two or three days, local officials came to our house trying to convince my mom to have me aborted. My parents exerted every means to delay the act, putting it off until my mom was almost in her eighth month of pregnancy.

One of my dad’s friends told him there is a type of medicine that can accelerate the labor process. My dad tapped his whole network, and managed to secretly arrange the injection before the abortion surgery.

The abortion was also done by injection, only with a huge needle, and the doctor used his hands to feel the position of the baby to make sure the injection would be fatal. Pretending that she was feeling unwell, my mom shifted around as much as she could in the hope to make the injections miss. Thanks to the earlier medicine and her intentional movements, the abortion didn’t kill me.

My mom gave birth to me in the hospital at three a.m. Afraid that the doctor would give another injection if he found out the baby was still alive, my mom gave birth in complete silence. She shared a ward with a dozen other patients, and no one knew she was having a baby coming out of her body, not even the lady whose bed was less than a meter away, until my cry broke out.

The hospital was located next to a river. My mom said she saw the bodies of dead babies floating over the river. Forced abortion was nothing surprising at that time. Regularly, I think of those babies whose lives were never able to blossom and grow. I am grief-stricken to picture the vivid and complex lives they could have had as we do.

Because I wasn’t supposed to be born, I’ve been a “black human being”—I didn’t have a hukou until the end of high school, when I needed an ID card to take the Gaokao.

My parents were both primary school teachers in our village. Different from most local parents, they valued education and were very strict. When my peers were running wild in nature, I was condemned to homework and books.

That was when I got into reading. I read almost every book that was available to me. Our primary school also had a very small library with a collection mostly of translated classics. I remember enjoying “Boule De Suif” and How the Steel Was Tempered.

I came to Beijing for school in 2014. Beijing experienced terrible pollution that year. Most of the winter days were heavily polluted and grey and suffocating. It was also that winter I lost my best friend. Two months after I started school, I got a phone call telling me she had a car accident.

I guess when you’re in your early twenties, the idea of a beloved one’s death is still quite outside your conceptual grasp. I don’t think losing her so early in life is something I will ever really get over, but I’d say the sadness has lost its sharpness over time. I believe that she remains as a part of me. As I live, she lives.

After that, I developed a new understanding of death and became more open-minded about it. I’m now reading a book about aging and dying, a discussion probably most of us fail to engage with enough. I think apart from learning how to love people, it’s even more important to learn how to take the moment to say goodbye.

I kind of feel being in an awkward age—I have the feeling of being young at the right time, yet occasionally I can’t help feeling like I’m running late to everything. The world around me just keeps changing at a dizzying speed.

Would I say I’m a happy person? No, not really. I wake up everyday feeling thankful for what I have. But I’m an idealist, which means I feel disappointed very often because apparently it’s not a perfect world we’re living in. Yet I also get so often amazed because the world stores so many surprises. With the circle of disappointment and amazement, there’s never a boring day. Every day I feel a new yearning for life.

Edited by David Huntington

我出生在一个江西的小村子,村子住了不到两百人,在村头喊话大点声,村尾就能听见。村子很偏,距离县城都两个多小时,去县城的班车每天只有一趟,大清早发车,搭车需要早晨5点多就起床,站在路边等。

我是家里的老小,有四个姐姐,这在年龄相近的人里面是很少见的。九十年代初那会儿计划生育很严,家里三天两头来人,劝我妈把我拿掉。我妈用尽各种办法,能拖一天是一天,一直拖到胎儿差不多8个月,才“同意”去县城的医院做引产手术。

我爸通过朋友打听到有一种药水注射之后可以帮助胎儿提前发动,他四处张罗,在手术之前,瞒着医生偷偷安排给我妈注射了这种助产药水。

引产也是注射药水,又大又粗满满的一针管,医生在打针时会用手感受胎儿的位置确保打到要害。我妈借故不舒服,在医生打针的时候不时假装不经意地挪动身体,就这样,打胎的药水才没能要了我的命。

我妈是在凌晨三点的时候生下我的。害怕医生发现胎儿还活着过来补针,她强忍着没有发出任何声音。她当时住的是公共病房,里面住了十几号人,没有人发现她在生孩子,旁边的病床隔了不到一米的距离,也没有察觉,直到我哇地发出哭声。

我妈当时住的医院旁边就是河,她说上面不时能看见漂浮着的婴儿尸体,打胎在当时太过正常,跟扔只小猫小狗似的。我常想到我妈说到的这些婴儿,常想象着他们未曾有机会体验的有一万种可能的人生。

因为属于严重超生,我小时候一直属于“黑人口“,名字没在我们家的户口本上,直到高考需要身份证,才补办了一个户口。

我父母都是我们当地的小学老师,跟大多数村里的家长不同,他们很重视教育,小时候其他小伙伴在光着脚丫乱跑树上抓知了河里逮鱼的时候,我被我妈关在家里写作业看书。

也就是那时候开始,我把家里有的书,该看的不该看的,都来回看了个遍。我们的小学也有个很小的图书室,里面的书可以借看,大多是一些翻译过来的名著,印象比较深的有莫泊桑的《羊脂球》, 还有《钢铁是怎样炼成的》。

我14年来北京上学。那年冬天北京的雾霾特别严重,几乎很少有晴朗的天,一般都是阴沉沉的,叫人透不过气。也就是在那年冬天,我失去了我最好的朋友。我来北京两个多月,收到她车祸去世的消息。

在你20岁出头的时候,你大概很少去考虑死亡这件事,总觉得离得很遥远。失去她是个永远不会痊愈的伤疤,但我坚信她的一部分住进了我的身体里,我活着就是她活着。她出事后,我对死亡也有了新的更开放的理解。我最近在看一本关于临终关怀的书,我想除了学会爱我们还应该学会告别。

二十多岁是个青黄不接的年龄,我有时觉得年轻正当其时,未来可期,有时又觉得这个世界在焦急地往前赶,而我却走得太慢了,好像什么都晚了一步。

我是否算得上是一个快乐的人?可能并不算。我很感恩我所拥有的一切,但是我太理想主义,当然也就意味着会不断失望,好在这个世界同时又有很多美好,所以这么一会儿失望一会儿憧憬的,倒也从没觉得生活无趣。

Kuang is the founder of Beijing Lights. She would love to hear your thoughts about the column and is open to new collaborations. She can be reached at kuang@spittooncollective.com.